34. 应对自杀意图

应对自杀意图

1. 危机电话咨询

危机电话咨询服务经常接到考虑自杀的人的电话,有时来电者在求助前已经服用了过量的处方药。同样,面对面的咨询师也会不可避免地遇到有自杀想法或倾向的人。大多数咨询师在与这样的人进行咨询时都会感到焦虑,与他们合作也不可避免地会有压力。

2. 伦理问题

在处理考虑自杀的人时,会涉及一些伦理问题。作为咨询师,在选择可接受的策略之前,你可能需要澄清自己对自杀的价值观。作为咨询师,我们最好不将自己的价值观强加给寻求帮助的人。然而,我们需要保持一致性和真诚,因此每个人都需要做必要的事情来满足自己的良心。此外,我们需要意识到任何法律义务和我们的行为的法律后果。我们必须记住,我们对每一个寻求我们帮助的人都负有照顾的责任,并且需要尊重我们工作的机构的政策。如果我们在处理考虑自杀的人时有内部冲突,那么我们需要解决这些冲突,以确保我们自己的福祉和他们的福祉。

3. 咨询师的责任

咨询师对寻求帮助的人负有照顾的责任。

4. 自杀权利的讨论

一个人是否有权选择自杀?你对这个问题的回答可能与奥利不同,我们的回答可能与寻求我们帮助的人的答案不同。我们建议你在培训小组中深入讨论这个问题(如果你在培训小组中),或与你的主管讨论,以便你对自己的态度和信念以及主管的期望有一个清晰的认识。这样你将更有能力帮助有自杀想法的人。

5. 咨询师的观点

我们认识到,一些咨询师认为,一个人在经过深思熟虑后有权选择自杀。然而,大多数咨询师强烈反对这一观点,认为坚决干预是正当和必要的,以防止自杀的发生。许多咨询师认为,考虑自杀的人可能暂时情绪紊乱,无法在当时做出理性的决定。这一信念得到了与曾经自杀但后来感谢咨询师的人的经验的支持,因为他们找到了生活的新的意义和满足感。因此,大多数咨询师认为,咨询师的照顾责任证明了坚决干预、强制住院和随后的精神病治疗的必要性,当其他选项失败时。显然,这里涉及照顾责任的问题,因为自杀是一条单程路,有自杀想法的人需要被认真对待。请记住,反复尝试自杀的人最终往往会成功。他们的求助声需要在为时已晚之前被听到。

考虑自杀的原因

1. 分类

考虑自杀的人大致可以分为四类,尽管其中三类在某种程度上有所重叠。

- 第一类:生活质量极差且看不到改善可能性的人。这类人包括慢性病患者、长期疼痛者、严重残疾者和/或极度贫困且几乎没有改变现状可能性的人。这些人常常严重抑郁,因看不到生活的理由而有极大的自杀风险,尤其是当他们孤独且缺乏足够的社会支持时。

- 第二类:最近经历过创伤的人。这类人在危机时期非常危险。这类人包括在第32章中描述的遭受损失的人。

- 第三类:那些用自杀言论或自杀行为作为最后手段,试图让他人听到或回应他们的痛苦的人。有时他们的目标是操纵他人的行为。他们仍然有真正的风险,但动机不同。他们对死亡往往有相当大的矛盾心理,可能并不真的想死。这类中的一些人公开地操纵他人,例如,可能会对离开他们的配偶说:“回来我身边,否则我会杀了自己。”

- 第四类:正在经历精神病发作并可能听到命令他们自杀的声音的人。显然,这些人需要紧急的精神病帮助。

2. 帮助的第一步

帮助的第一步是尝试理解这个人的当前思维。

3. 可能的原因

我们列出了一些可能的原因,说明一个人为什么可能会考虑或谈论自杀的可能性。当你阅读这份清单时,你可能希望思考是否还有其他未包括的原因。可能的原因包括:

- 因为他们对现状感到绝望,无法看到解决问题的替代方案,这些问题对他们来说似乎是无解的、无法忍受的和无法逃避的。

- 因为他们情绪紊乱,害怕自己可能会自杀,希望被阻止。

- 作为一种声明。

- 作为一种伤害他人的方法;愤怒的终极表达。

- 当其他方法失败时,作为最后的努力,引起对看似不可能情况的注意。

- 操纵他人。

- 因为他们已经积极决定自杀,想要实施并希望其他人理解其行动的理由。

- 在死亡前或死亡时与另一个人接触。

- 作为一种告别,为死亡做准备。

- 因为他们正在经历精神病发作,听到命令他们自杀的声音。

自杀风险评估

1. 风险识别

任何说生活不值得继续下去的人都可能处于某种程度的风险中。然而,许多没有自杀意图的人在绝望时也会开始质疑生活的价值。咨询师面临的挑战是确定特定人的风险水平。在这种情况下,经验可以帮助估计风险水平,决定是否需要采取行动,以及如果需要采取行动,选择采取什么行动。因此,新咨询师需要与他们的主管咨询。

2. 与主管咨询的重要性

在评估风险水平时,与主管咨询是非常有帮助的。

3. 风险因素

在相关文献中,有一些因素被认为有助于确定风险水平(见本章末尾的进一步阅读建议)。以下是几个常见的风险因素:

-

性别和种族 尽管女性自杀未遂的次数多于男性,但男性自杀成功的风险更高。特别是在澳大利亚,土著男性的自杀风险较高。

-

年龄 年轻人和老年人更有可能自杀,风险在18岁以下和45岁以上的人群中更高。

-

强烈的自杀念头 每当一个人想到自杀时,假设存在某种程度的风险是明智的。然而,如果这些念头持续存在或强烈,且几乎没有矛盾心理,风险就会增加。

-

预警信号 自杀的人通常在一段时间内发出预警信号。不幸的是,有时这些信号被忽视,因为它们可能多次出现,被错误地视为不会付诸行动的威胁。

-

有自杀计划 如果制定了一个现实的自杀计划,那么显然这个人已经超出了模糊地认为生活不值得继续的想法,存在真实的自杀风险,计划可能会被实施。

-

选择致命的方法 一些自杀方法比其他方法更容易达到完成,因为它们快速或在接近死亡时提供很少的撤回机会。例如,当一个人使用枪支或从高处跳下时。

-

方法的可用性 如果一个人已经有了实施计划的手段,风险会更高。例如,如果一个人有一把装满子弹的枪,或者有足够的药片可以致死,那么计划可能会被实施。

-

救援难度 如果其他人难以干预和阻止自杀企图,风险会增加。例如,当一个人在孤立的地方,位置未知,或有人爬上了结构物,使其他人难以跟随时。

-

孤独和缺乏支持 孤独、单身或分居的人,认为没有人关心他们,容易陷入抑郁和自杀念头及行为。他们也更容易在没有干扰的情况下实施自杀计划。

之前的自杀尝试

之前的自杀尝试是风险增加的指示。特别是如果这些尝试频繁、最近发生且严重。

家人、朋友或同事自杀

如果家庭成员、亲密朋友、同事或同龄人自杀,自杀风险会增加。此外,如果亲人或宠物去世,也可能存在风险。

听关于死亡的歌曲

一些人,特别是年轻人,倾向于痴迷地听关于死亡、垂死和自杀的歌曲。这会增加风险。

抑郁

感到绝望、无助或绝望的人有自杀风险。特别是严重的抑郁症,可能伴有失眠或饮食障碍等症状。

精神病史

精神病史或疾病是风险增加的另一个指示。

理性思维丧失

理性思维丧失可能由多种原因引起。受到创伤、受酒精或药物影响、患有痴呆症或精神疾病的人可能无法理性思考。因此,他们呈现出更高的风险,咨询师也有明确的照顾责任。

无明显原因的情绪好转

如果某人表现出严重的抑郁情绪和自杀念头,然后突然变得平静并有一种满足感,但没有明显的原因,这可能是非常高风险的迹象。这个人可能已经完成了自杀的准备工作,并因计划中的逃离急性情绪痛苦而感到解脱。通过让咨询师相信一切现在都好,他们可能会误导咨询师,从而不采取预防措施。

赠送财物和处理事务

赠送个人财物、立遗嘱或终止租约等行为可能是该人正在准备自杀并处于高风险的迹象。

医疗问题

严重影响生活质量、疼痛或危及生命的医疗问题会增加自杀风险。慢性疾病且几乎没有治愈或缓解的希望可能会增加一个人结束生命的愿望。这里既有价值观问题,也有照顾责任问题,因为有些人坚信自愿安乐死是道德上正当的,而另一些人则强烈反对。

物质滥用

过度使用酒精或药物,无论是非法的还是合法处方的,都会增加自杀风险。确实,酒精或其他物质滥用与自杀完成有关。

人际关系问题

认为自己被困在高度功能失调的关系中且无法离开的人有更高的自杀风险。同样,关系破裂、分居、离婚过程中的人都有风险。当关系因再婚、进入新的继家庭、家庭中有新生儿或孩子离家等情况发生变化时,风险也可能增加。

生活方式或日常的变化

许多人难以适应生活方式或日常的变化,因此变化时期可能导致自杀念头和风险增加。例如,当一个人换工作、换学校或搬家时。当一个人搬到新地方,可能会失去与长期朋友的联系,这一点尤其相关。

财务问题

涉及贫困、失业和财务困难的问题,当相关人士感到沮丧且无力改变现状时,会导致风险增加。重要例子包括破产和失去生意或住房的情况。

创伤和虐待

创伤事件和过去及现在的虐待或感知到的虐待经历,可能增加自杀风险。这包括情感、身体、性和社会虐待。

损失

所有重要的损失都会增加自杀风险。例如,重要关系的丧失、工作的丧失、就业机会的丧失、生意的丧失、住房的丧失、财产的丧失、自尊的丧失和角色的丧失。在工作或学术上失败,或认为自己辜负了他人的人,可能会遭受自尊的损失。

辅导策略

对于新咨询师来说,帮助有自杀念头的人时最大的问题是咨询师自身的焦虑。有时,新咨询师会试图将人从自杀话题上转移开,而不是鼓励他们将自己的自毁想法公开并妥善处理。不幸的是,这样的回避问题可能会增加自杀尝试的可能性。

图34.1 自杀风险评估

风险因素 - 在有风险的地方打勾

- □ 性别

- □ 年龄

- □ 种族背景

- □ 医疗问题

- □ 强烈和/或频繁的自杀念头

- □ 在一段时间内发出的预警信号

- □ 有自杀计划

- □ 选择致命的方法

- □ 方法的可用性

- □ 救援难度

- □ 孤独或独处

- □ 缺乏支持

- □ 重要的生活变化事件

- □ 生活方式和/或日常的变化

- □ 工作、学校或住所的变化

- □ 之前的自杀尝试

- □ 朋友、同龄人、同事或家庭成员已完成自杀

- □ 痴迷地听关于死亡、垂死或自杀的歌曲

- □ 亲人、朋友或宠物的死亡

- □ 抑郁

- □ 精神病史或疾病

- □ 理性思维丧失

- □ 无明显原因的情绪好转

- □ 赠送财物

- □ 处理事务

- □ 关系高度功能失调

- □ 关系破裂、分居或离婚

- □ 关系变化 - 再婚、新的继家庭、新增加的孩子、孩子离家

- □ 关系担忧 - 担心失去家庭成员或伴侣,或担心某人无法应对

- □ 酒精和/或药物滥用

- □ 财务问题

- □ 社会经济状况

- □ 创伤

- □ 虐待或感知到的虐待 - 过去或现在的感情、身体、性或社会虐待

- □ 失业或就业机会的丧失

- □ 事业、住房或财产的丧失

- □ 自尊的丧失 - 在工作或学术上失败,或认为自己辜负了他人

- □ 角色的丧失

- □ 其他未列出的因素

将自杀念头公开化

每当咨询一个抑郁或焦虑的人时,咨询师需要寻找可能表明该人可能正在考虑自杀的最微小线索。人们往往不愿意直接说“我想杀死自己”,而是倾向于用不那么具体的方式表达,比如“我不再享受生活”或“我对生活厌倦了”。当一个人做出这样的陈述时,咨询师直接问他们,“你在考虑自杀吗?”是有道理的。这样,自杀念头就被公开化,可以得到适当的处理。我们需要记住,许多人一生中某些时候对是否想活下去持矛盾态度,而且许多人在拒绝之前会考虑自杀的可能性。

处理你自己的感受

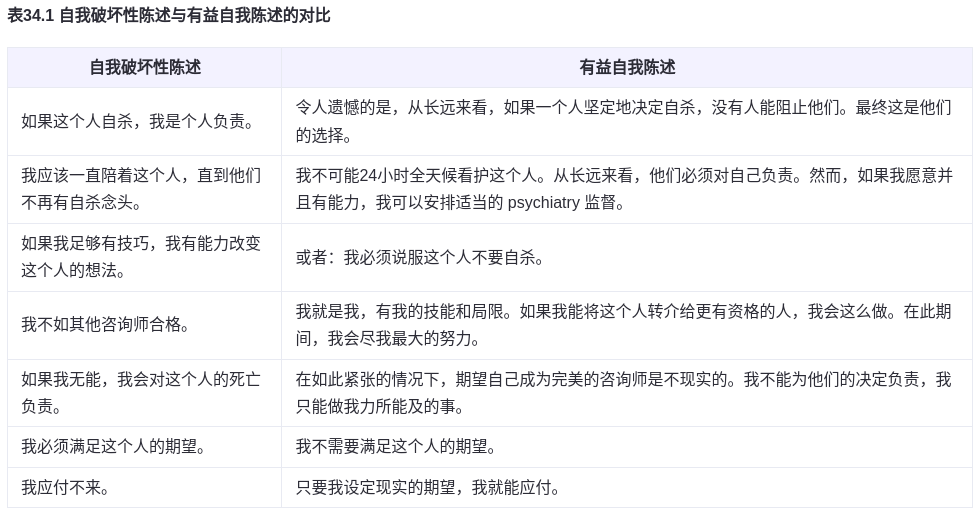

如果你在听到某人说他们在考虑自杀时没有感到情绪紧张,那你就非常不寻常了。作为咨询师,允许自己体验这些感受,然后你才能决定如何处理它们。 这些感受可能源于你给自己传递的无益信息,如表34.1所列。如果是这样,你可以给自己新的信息,摒弃那些可能导致你紧张的自我破坏性信息。表34.1展示了一些典型的情况下的自我破坏性和替代的有益自我陈述。 挑战你的自我破坏性想法,如果紧张感没有消退,咨询你的主管。

咨询技巧

以前学到的微观技能,加上适当的咨询关系,是帮助考虑自杀的人的基本工具。我们建议最初要集中精力建立与对方的关系,以便在建立了信任之后,他们可以坦率地谈论自己的感受和意图。咨询师可以通过说,“我关心你的安全和福祉,了解你为何会有这样的感受非常重要。”来邀请他们这样做。通过这种方法,对方可能会意识到咨询师是在与他们一起探索他们的感受、想法和选择,而不是与他们对立。

咨询关系 在面对自杀念头时 可以是一个宝贵的资源

关注个体的矛盾心理

我们认识到每位咨询师都需要根据自身情况决定如何咨询有自杀倾向的个体。有些咨询师更倾向于采用直接的方法,试图说服当事人不要自杀,对于某些人来说,这可能是最有效的方法。然而,我们认为这并不总是最佳选择,因为它可能导致咨询师与当事人产生对立。相反,我们认为,通常更有益的是专注于建立与当事人的关系,然后探讨他们的矛盾心理——“我是否应该自杀?”大多数,甚至所有,有自杀念头的人都对死亡持有某种程度的矛盾心理。如果一个人100%确信自己要自杀,他们可能就不会来找咨询师,而是直接实施自杀计划。我们发现,专注于个体与个体之间的咨询关系,同时探讨当事人的矛盾心理,往往是成功咨询那些考虑自杀者的关键。

表34.1 咨询师寻求帮助有自杀念头的人时,自我毁灭性和有益的自我陈述对比

| 自我毁灭性陈述 | 有益的自我陈述 |

|---|---|

| 如果这个人自杀,我是有责任的。 | 长远来看,如果一个人坚定地决定要自杀,没有人能阻止他们。最终这是他们的选择。 |

| 我应该一直陪伴这个人,直到他们不再有自杀念头。 | 我不可能一天24小时看着这个人。长远来看,他们必须对自己负责。然而,如果我希望并且有能力,我可以采取措施安排适当的精神科监督。 |

| 如果我足够有技巧,我有能力改变这个人的想法。 | 或者 |

| 我必须说服这个人不要自杀。 | 我没有能力改变别人的想法。我能做的最多就是帮助他们探讨涉及的问题,然后采取其他可行的行动。 |

| 我不如其他咨询师有资格。 | 我是我,有自己的技能和局限。如果我能将这个人转介给更有资格的人,我会这样做,与此同时,我会尽我最大的努力。 |

| 如果我不称职,我将对这个人的死亡负责。 | 在如此紧张的情况下,期望自己成为完美的咨询师是不现实的。我不能对他们的决定负责,我只能做我能做到的事情。 |

| 我必须满足这个人的期望。 | 我不需要满足这个人的期望。 |

| 我无法应对。 | 只要我为自己设定现实的期望,我就能应对。 |

探讨当事人的选择

正如第25章所述,当一个人在两个选项之间做出选择时,会失去其中一个选项,并且可能还要为选择的选项付出代价。选择自杀意味着失去生命、与他人的联系以及与他人交流自己痛苦的机会。此外,如果他们对更好的未来抱有任何希望,也会失去这种希望。死亡的代价可能包括对未知的恐惧,对于一些宗教人士来说,还包括因自杀而受到惩罚的恐惧。

我们认为,在许多情况下,让考虑自杀的人意识到自己的矛盾心理,并帮助他们审视死亡和生活的后果、成本和收益是有利的。尽管在某个阶段我们可能会决定,出于职责需要采取坚定的干预措施,但在最初阶段,我们尽量避免直接施压要求他们活下去,而是帮助他们探讨自己的选择。这样,当事人可能会感到被理解,有机会处理自己的痛苦,并可能感到足够被重视,从而重新考虑他们的决定。

通过与当事人一起,他们可以自由地探索“我想死”这部分自我和相反的极性,咨询师在一旁陪伴他们进行探索。

个人需要充分探索自我毁灭性想法

一个人需要充分探索自己的自我毁灭性想法,才能改变它们。

直接方法

直接方法是试图说服考虑自杀的人,活着是最好的选择。这种方法通常不是我们的首选,因为它会在说“我想死”的人和说“我希望你活下去”的咨询师之间造成争斗。咨询师需要施加巨大的压力来说服当事人选择生活,而这种压力可能会很困难,因为咨询师和当事人是对立的而不是合作的。即便如此,这种方法对某些人来说可能是成功的。没有普遍的“正确方法”。每个人都是独特的,每个咨询师也是如此。每个咨询师都需要选择一种对自己和寻求帮助的人合适的方法。如果咨询师专注于建立和维持稳固的个人与个人之间的咨询关系,那么他们就优化了成功的可能性。如果这种方法不成功,职责要求咨询师在与主管协商后采取行动,确保当事人的安全和福祉。

应对抑郁和愤怒

考虑自杀的人通常处于深深的抑郁状态,正如第31章所述,抑郁症通常是由于被压抑的愤怒引起的。有时,考虑自杀的人可能会将本应适当地指向他人的愤怒转向自己。询问“你对谁感到愤怒?”这个问题可能会有帮助。如果当事人回答“我自己”,你可以同意这显然是与想要自杀一致的。你可以说,“你对自己如此愤怒,以至于想通过自杀来惩罚自己。”将自杀视为自我惩罚而不是逃避的重新框架,在某些情况下可能有助于引发改变。然后你可以问,“除了你自己,你最对谁感到愤怒?”通过这样做,如果你能帮助当事人表达他们的愤怒,并将其从自己转移到其他人身上,他们的抑郁和自杀念头可能会减轻。然而,重要的是要记住,作为咨询师,确保寻求帮助的人不会对他人构成威胁是非常重要的。

探讨个体的选择

正如第25章所述,当一个人在两个选项之间做出选择时,他们将失去其中一个选项,并可能为所选选项付出代价。选择自杀意味着失去生命、与他人的联系以及与他人交流痛苦的机会。此外,如果他们对未来的美好有所期待,这些希望也会消失。死亡的成本可能包括对未知的恐惧,对于一些宗教人士来说,还包括因自杀而受到惩罚的恐惧。

我们认为,在许多情况下,让考虑自杀的人意识到他们的矛盾心理,并帮助他们审视死亡和生活的后果、成本和收益是有利的。尽管在某些阶段我们可能认为职责要求采取坚决的干预措施,但在最初阶段,我们尽量避免直接施压让当事人活下去,而是帮助他们探索他们的选择。这样,当事人可能会感到被理解,有机会处理他们的痛苦,并可能感到足够被重视,从而重新考虑他们的决定。

通过与当事人一起,他们可以自由地探索“我想死”这一部分自我及其对立面,咨询师在此过程中陪伴他们。

一个人需要充分探索他们的自毁性想法,才能改变这些想法。

直接方法

直接方法是试图说服考虑自杀的人,活着是最好的选择。这种方法通常不是我们的首选,因为它会在说“我想死”的人和说“我希望你活”的咨询师之间引发争斗。咨询师需要施加巨大压力来说服当事人生活的正确性,而这可能很困难,因为咨询师和当事人处于对立而不是合作的状态。即便如此,这种方法对某些人来说可能是成功的。没有普遍的“正确方法”,每个人都是独特的,每个咨询师也是如此。每个咨询师都需要选择一个对他们和寻求帮助的当事人来说合适的方法。如果咨询师专注于建立和维护稳固的个人与个人之间的咨询关系,那么他们就优化了成功的可能性。当这种方法不成功时,职责要求咨询师采取行动,在与主管协商后确保当事人的安全和福祉。

应对抑郁和愤怒

考虑自杀的人通常处于深深的抑郁中,正如第31章所述,抑郁通常是由于被压抑的愤怒引起的。有时,考虑自杀的人可能将本应适当地指向他人的愤怒转向自己。问“你对谁生气?”这个问题可能有用。如果当事人回答“我自己”,你可以同意这一点,并指出这与想要自杀是一致的。你可以说,“你对自己如此愤怒,以至于想通过自杀来惩罚自己。”将自杀视为自我惩罚而非逃避的重新框架在某些情况下可能有助于产生变化。然后你可以问,“除了你自己,你还对谁最生气?”如果通过这种方式你能帮助当事人表达他们的愤怒,并将其从自己身上转移到其他人身上,他们的抑郁和自杀念头可能会减轻。然而,重要的是要记住,作为咨询师,你必须尽最大努力确保寻求你帮助的当事人不会对他人构成威胁。

寻找触发点

另一种进入一个人内心世界的方法是找出今天引发自杀念头的触发点。很多时候,单一事件是触发点,这个触发点有时可以提供关于该人意图的重要线索。例如,该人的意图是否部分是为了惩罚让他们生气或受伤的人?如果是这样,探讨相关问题可能会有用。

签订协议

在与有自杀念头的人一起处理相关问题后,许多咨询师鼓励这些人签署一份合同,同意如果强烈的自杀念头再次出现,他们不会在回来接受咨询前自杀。虽然我们自己不使用书面合同,但我们确实与这些人协商,以获得口头协议,明确他们如果强烈的自杀念头再次出现将采取什么行动。我们探讨他们在感到再次有自杀冲动时可能寻求的帮助的替代方案。我们询问他们首先会尝试联系谁,如果第一个人不在,他们还可以联系谁,或者他们会去哪里寻求帮助。在寻求口头协议时,我们依赖于咨询关系的力量,明确表示这个人对我们很重要,我们相信他们能够遵守协议。

认识到你的局限性

不要忘记,不幸的是,期望一个人一定会选择继续生活是不现实的。虽然你可以在短期内采取措施确保这个人活着,但从长远来看,如果他们决心自杀,他们很可能会成功。然而,随着咨询的进展,你需要与主管协商,决定是否需要采取直接行动来防止自杀。这是一个重大的决定,肯定会受到你自己的价值观和雇佣你的机构价值观的影响。在某些情况下,采取行动的决定是明确的。例如,让因暂时的精神疾病或突然的创伤而心理受扰的人自杀而不采取坚决和积极的行动来阻止他们是不道德和不负责任的。认真考虑自杀的人可能需要有技能的专业人士提供的长期心理治疗,因此要做好适当的转介准备。这样的人最终的福祉取决于他们能否对其思维方式和生活方式做出重大改变,而这不太可能在一次咨询中实现。

在某些情况下

我们的 护理职责 要求坚决的直接行动

学习总结

经常重复自杀企图的人最终往往能够成功自杀。自杀者包括那些陷入悲惨生活的人、最近经历过创伤的人以及那些试图操纵他人的人。 在咨询自杀者时,作为咨询师,处理自己的感受并挑战任何可能存在的非理性信念非常重要。 在咨询考虑自杀的人时,应重点关注咨询关系,使用常规的咨询技巧:

- 了解是什么触发了自杀念头

- 将当事人的愤怒带入焦点

- 如果有用,抓住当事人的矛盾心理

- 探讨当事人的选择,特别是死亡的成本

- 如果认为直接对抗的方法更有可能有效,可以使用

- 决定采取哪些直接行动以防止自杀

- 尽可能将当事人转介给合适的专业人士。

进一步阅读

Duffy, D. & Ryan, T. (编) 2004, 预防自杀的新方法:从业者手册, Jessica Kingsley, 伦敦. Henden, J. 2008, 预防自杀:解决方案聚焦方法, Wiley, 奇切斯特. Reeves, A. 2010, 咨询自杀客户, SAGE, 伦敦.

本章知识点阐述

[进一步阐述知识点

- 危机电话咨询

- 常见情况:危机电话咨询服务经常接到考虑自杀的人的电话,有时来电者在求助前已经服用了过量的处方药。

- 面对面咨询:面对面的咨询师也会不可避免地遇到有自杀想法或倾向的人。

- 咨询师的压力:大多数咨询师在与这样的人进行咨询时都会感到焦虑,与他们合作也不可避免地会有压力。

- 伦理问题

- 价值观澄清:在处理考虑自杀的人时,会涉及一些伦理问题。作为咨询师,需要澄清自己对自杀的价值观。

- 不强加价值观:虽然我们最好不将自己的价值观强加给寻求帮助的人,但我们需要保持一致性和真诚。

- 法律义务:我们需要意识到任何法律义务和我们的行为的法律后果。

- 照顾责任:我们必须记住,我们对每一个寻求我们帮助的人都负有照顾的责任,并且需要尊重我们工作的机构的政策。

- 内部冲突:如果我们在处理考虑自杀的人时有内部冲突,需要解决这些冲突,以确保我们自己的福祉和他们的福祉。

- 咨询师的责任

- 照顾责任:咨询师对寻求帮助的人负有照顾的责任。

- 自杀权利的讨论

- 个人权利:一个人是否有权选择自杀?这个问题的回答因人而异。

- 讨论和反思:建议在培训小组中深入讨论这个问题,或与主管讨论,以便你对自己的态度和信念以及主管的期望有一个清晰的认识。

- 提高能力:这样你将更有能力帮助有自杀想法的人。

- 咨询师的观点

- 不同观点:一些咨询师认为,一个人在经过深思熟虑后有权选择自杀。然而,大多数咨询师强烈反对这一观点。

- 坚决干预:大多数咨询师认为,坚决干预是正当和必要的,以防止自杀的发生。

- 情绪紊乱:许多咨询师认为,考虑自杀的人可能暂时情绪紊乱,无法在当时做出理性的决定。

- 成功案例:这一信念得到了与曾经自杀但后来感谢咨询师的人的经验的支持,因为他们找到了生活的新的意义和满足感。

- 照顾责任:因此,大多数咨询师认为,咨询师的照顾责任证明了坚决干预、强制住院和随后的精神病治疗的必要性,当其他选项失败时。

- 单程路:显然,这里涉及照顾责任的问题,因为自杀是一条单程路,有自杀想法的人需要被认真对待。

- 反复尝试:请记住,反复尝试自杀的人最终往往会成功。他们的求助声需要在为时已晚之前被听到。

总结 应对自杀意图是一项复杂且充满挑战的任务,咨询师需要在伦理、法律和专业责任之间找到平衡。通过澄清自己的价值观、保持一致性和真诚、尊重法律义务和机构政策,咨询师可以更有效地帮助有自杀想法的人。坚决干预和提供支持不仅是为了保护当事人的生命,也是为了帮助他们找到生活的新的意义和满足感。在实际工作中,咨询师需要不断学习和提升自己的专业素养,以应对各种复杂的自杀危机情况。]

[进一步阐述知识点

- 分类

- 第一类:生活质量极差且看不到改善可能性的人。这类人包括慢性病患者、长期疼痛者、严重残疾者和/或极度贫困且几乎没有改变现状可能性的人。这些人常常严重抑郁,因看不到生活的理由而有极大的自杀风险,尤其是当他们孤独且缺乏足够的社会支持时。

- 特点:长期的生活困境和缺乏希望。

- 风险因素:严重抑郁、孤独、缺乏社会支持。

- 第二类:最近经历过创伤的人。这类人在危机时期非常危险。这类人包括在第32章中描述的遭受损失的人。

- 特点:近期遭受重大打击或创伤。

- 风险因素:情感冲击、心理创伤、应对能力不足。

- 第三类:那些用自杀言论或自杀行为作为最后手段,试图让他人听到或回应他们的痛苦的人。有时他们的目标是操纵他人的行为。他们仍然有真正的风险,但动机不同。他们对死亡往往有相当大的矛盾心理,可能并不真的想死。

- 特点:用自杀作为沟通工具或操纵手段。

- 风险因素:情感矛盾、操纵动机、寻求关注。

- 第四类:正在经历精神病发作并可能听到命令他们自杀的声音的人。显然,这些人需要紧急的精神病帮助。

- 特点:精神病症状,幻听等。

- 风险因素:精神病发作、幻听、认知障碍。

- 帮助的第一步

- 理解当前思维:帮助的第一步是尝试理解这个人的当前思维。了解他们的想法和感受,可以帮助咨询师更好地评估风险并制定合适的干预措施。

- 可能的原因

- 绝望:因为对现状感到绝望,无法看到解决问题的替代方案,这些问题对他们来说似乎是无解的、无法忍受的和无法逃避的。

- 应对策略:提供希望,帮助他们看到解决问题的其他途径。

- 情绪紊乱:因为情绪紊乱,害怕自己可能会自杀,希望被阻止。

- 应对策略:提供支持和安慰,帮助他们管理情绪。

- 声明:作为一种声明。

- 应对策略:倾听和理解,提供情感支持。

- 伤害他人:作为一种伤害他人的方法;愤怒的终极表达。

- 应对策略:帮助他们表达愤怒,寻找更健康的应对方式。

- 引起注意:当其他方法失败时,作为最后的努力,引起对看似不可能情况的注意。

- 应对策略:提供支持,帮助他们找到其他表达方式。

- 操纵他人:操纵他人。

- 应对策略:明确界限,提供非操纵性的支持。

- 积极决定:因为他们已经积极决定自杀,想要实施并希望其他人理解其行动的理由。

- 应对策略:坚决干预,提供紧急帮助。

- 与他人接触:在死亡前或死亡时与另一个人接触。

- 应对策略:提供陪伴和支持,帮助他们表达未尽的心愿。

- 告别:作为一种告别,为死亡做准备。

- 应对策略:提供情感支持,帮助他们完成未竟之事。

- 精神病发作:因为他们正在经历精神病发作,听到命令他们自杀的声音。

- 应对策略:提供紧急精神病帮助,确保安全。

总结 考虑自杀的原因多种多样,咨询师需要在分类和理解的基础上,采取合适的干预措施。通过倾听和理解,提供支持和帮助,咨询师可以有效地帮助有自杀想法的人,降低自杀风险,提高他们的生活质量和幸福感。在实际工作中,咨询师需要不断学习和提升自己的专业素养,以应对各种复杂的自杀危机情况。]

[进一步阐述知识点

- 风险识别

- 普遍现象:任何说生活不值得继续下去的人都可能处于某种程度的风险中。

- 常见误解:许多没有自杀意图的人在绝望时也会开始质疑生活的价值。

- 咨询师的挑战:咨询师需要确定特定人的风险水平,这需要经验和判断力。

- 新咨询师的建议:新咨询师需要与他们的主管咨询,以获得更多的支持和指导。

- 与主管咨询的重要性

- 专业支持:与主管咨询可以帮助咨询师更好地评估风险,决定是否需要采取行动,以及选择合适的行动方案。

- 经验分享:主管的经验和专业知识可以为新咨询师提供宝贵的指导。

- 风险因素

- 性别和种族

- 女性与男性:女性自杀未遂的次数多于男性,但男性自杀成功的风险更高。

- 特定群体:在澳大利亚,土著男性的自杀风险较高。

- 应对策略:关注特定群体的心理健康问题,提供针对性的支持和干预。

- 年龄

- 高风险年龄段:年轻人和老年人更有可能自杀,风险在18岁以下和45岁以上的人群中更高。

- 应对策略:加强对这些年龄段人群的心理健康教育和支持。

- 强烈的自杀念头

- 持续和强烈的念头:每当一个人想到自杀时,假设存在某种程度的风险是明智的。如果这些念头持续存在或强烈,且几乎没有矛盾心理,风险就会增加。

- 应对策略:密切关注这些人的心理状态,提供及时的心理支持和干预。

- 预警信号

- 常见的预警信号:自杀的人通常在一段时间内发出预警信号,如言语上的暗示、行为上的变化等。

- 应对策略:认真对待这些预警信号,及时进行干预。

- 有自杀计划

- 具体的计划:如果制定了一个现实的自杀计划,那么显然这个人已经超出了模糊地认为生活不值得继续的想法,存在真实的自杀风险,计划可能会被实施。

- 应对策略:迅速评估计划的具体性,采取紧急干预措施。

- 选择致命的方法

- 高风险方法:一些自杀方法比其他方法更容易达到完成,因为它们快速或在接近死亡时提供很少的撤回机会。例如,使用枪支或从高处跳下。

- 应对策略:了解和识别这些高风险方法,采取预防措施。

- 方法的可用性

- 手段的易得性:如果一个人已经有了实施计划的手段,风险会更高。例如,如果一个人有一把装满子弹的枪,或者有足够的药片可以致死,那么计划可能会被实施。

- 应对策略:限制高风险手段的可得性,提供安全的环境。

- 救援难度

- 难以干预:如果其他人难以干预和阻止自杀企图,风险会增加。例如,当一个人在孤立的地方,位置未知,或有人爬上了结构物,使其他人难以跟随时。

- 应对策略:加强社区和家庭的支持,提供及时的援助。

- 孤独和缺乏支持

- 社会支持的重要性:孤独、单身或分居的人,认为没有人关心他们,容易陷入抑郁和自杀念头及行为。他们也更容易在没有干扰的情况下实施自杀计划。

- 应对策略:提供情感支持和社交支持,帮助他们建立社会联系。

总结 自杀风险评估是一个复杂的过程,需要咨询师具备丰富的经验和专业知识。通过识别和评估各种风险因素,咨询师可以更有效地帮助有自杀风险的人,降低自杀风险,提高他们的生活质量和幸福感。在实际工作中,咨询师需要不断学习和提升自己的专业素养,以应对各种复杂的自杀危机情况。同时,与主管的咨询和支持也是非常重要的,可以帮助咨询师更好地应对挑战。]

[进一步阐述知识点

生活方式或常规的变化

- 风险增加:生活方式或常规的变化可能导致人们感到不安和不确定,这种不安感可能引发自杀念头。

- 应对策略:提供情感支持和适应性建议,帮助他们建立新的社会联系,减少孤独感和不安感。

经济问题

- 风险增加:经济问题可能导致严重的心理压力和绝望感,增加自杀风险。

- 应对策略:提供经济援助和心理支持,帮助他们寻找解决问题的方法,增强应对能力。

创伤和虐待

- 风险增加:创伤和虐待可能导致严重的心理创伤,增加自杀风险。

- 应对策略:提供创伤后应激障碍(PTSD)的治疗和支持,帮助他们处理创伤经历。

损失

- 风险增加:任何形式的损失都可能导致严重的心理痛苦和绝望感,增加自杀风险。

- 应对策略:提供心理支持和辅导,帮助他们重建自尊心,找到新的目标和意义。

图34.1 自杀风险评估

- 风险因素评估:图34.1提供了一个详细的自杀风险评估表,帮助咨询师识别和评估各种风险因素。

- 注意事项:虽然评估表提供了一种结构化的评估方法,但每个个体都是独特的,因此需要结合具体情况进行综合判断。

咨询策略

- 咨询师的焦虑:新咨询师在处理自杀话题时可能会感到焦虑,这可能影响他们的判断和干预效果。

- 应对策略:咨询师需要克服自己的焦虑,鼓励当事人坦诚地表达自杀念头,并提供适当的支持和干预措施。与主管咨询和支持也是非常重要的。 ]

总结 自杀风险评估是一个复杂的过程,需要综合考虑多个因素。通过识别和评估这些风险因素,咨询师可以更有效地帮助有自杀风险的人,降低自杀风险,提高他们的生活质量和幸福感。在实际工作中,咨询师需要不断学习和提升自己的专业素养,以应对各种复杂的自杀危机情况。同时,与主管的咨询和支持也是非常重要的,可以帮助咨询师更好地应对挑战。

[进一步阐述知识点

1. 将自杀念头公开化

-

寻找线索:咨询师需要寻找可能表明该人可能正在考虑自杀的最微小线索。人们往往不愿意直接说“我想杀死自己”,而是倾向于用不那么具体的方式表达,比如“我不再享受生活”或“我对生活厌倦了”。

-

进一步阐述:

- 风险识别:细微的线索可能包括言语上的暗示、行为上的变化、情绪上的波动等。咨询师需要保持高度的敏感性和观察力,及时捕捉这些线索。

- 倾听技巧:通过倾听和观察,咨询师可以更好地理解当事人的内心世界,从而发现潜在的自杀风险。

-

进一步阐述:

-

直接提问:当一个人做出这样的陈述时,咨询师直接问他们,“你在考虑自杀吗?”是有道理的。这样,自杀念头就被公开化,可以得到适当的处理。

-

进一步阐述:

- 减少误解:直接提问可以减少误解和猜测,使咨询师能够更准确地评估风险。

- 建立信任:通过直接提问,咨询师展示了对当事人的关心和支持,有助于建立信任关系。

-

进一步阐述:

-

矛盾心态:我们需要记住,许多人一生中某些时候对是否想活下去持矛盾态度,而且许多人在拒绝之前会考虑自杀的可能性。

-

进一步阐述:

- 理解复杂性:自杀念头往往是复杂和矛盾的,咨询师需要理解这种复杂性,避免简单的二元对立。

- 提供支持:通过理解当事人的矛盾心态,咨询师可以提供更全面的支持,帮助他们处理内心的冲突。

-

进一步阐述:

2. 处理你自己的感受

-

情绪紧张:如果你在听到某人说他们在考虑自杀时没有感到情绪紧张,那你就非常不寻常了。作为咨询师,允许自己体验这些感受,然后你才能决定如何处理它们。

-

进一步阐述:

- 自我觉察:承认和接受自己的情绪反应是处理自杀话题的重要一步。这有助于咨询师保持冷静和专业。

- 情感管理:通过自我觉察,咨询师可以更好地管理自己的情绪,避免被当事人的情绪所影响。

-

进一步阐述:

-

自我破坏性信息:这些感受可能源于你给自己传递的无益信息,如表34.1所列。如果是这样,你可以给自己新的信息,摒弃那些可能导致你紧张的自我破坏性信息。

-

进一步阐述:

- 挑战消极思维:识别和挑战自我破坏性信息,如“我无法处理这种情况”或“我帮不了他们”,可以帮助咨询师减少焦虑。

- 积极自我对话:通过积极的自我对话,咨询师可以增强自信,更好地应对挑战。

-

进一步阐述:

-

挑战自我破坏性想法:挑战你的自我破坏性想法,如果紧张感没有消退,咨询你的主管。

-

进一步阐述:

- 专业支持:在处理自杀风险时,咨询师需要寻求主管的支持和指导,以确保自己能够有效地应对。

- 持续学习:通过与主管的讨论,咨询师可以不断学习和提升自己的专业素养,更好地应对复杂的自杀危机情况。

-

进一步阐述:

3. 咨询技巧

-

基本工具:以前学到的微观技能,加上适当的咨询关系,是帮助考虑自杀的人的基本工具。

-

进一步阐述:

- 技能应用:倾听、共情、提问等微观技能在处理自杀风险时尤为重要,可以帮助咨询师更好地理解当事人的感受和需求。

- 综合运用:将这些技能综合运用于咨询关系中,可以提高干预的效果。

-

进一步阐述:

-

建立信任:我们建议最初要集中精力建立与对方的关系,以便在建立了信任之后,他们可以坦率地谈论自己的感受和意图。

-

进一步阐述:

- 关系重要性:建立信任关系是咨询过程的基础,有助于当事人更愿意分享自己的内心世界。

- 积极倾听:通过积极倾听和共情,咨询师可以建立起与当事人的良好关系,增强他们的安全感和信任感。

-

进一步阐述:

-

邀请谈话:咨询师可以通过说,“我关心你的安全和福祉,了解你为何会有这样的感受非常重要。”来邀请他们这样做。通过这种方法,对方可能会意识到咨询师是在与他们一起探索他们的感受、想法和选择,而不是与他们对立。

-

进一步阐述:

- 表达关心:通过表达关心和支持,咨询师可以减少当事人的防御心理,鼓励他们开放地谈论自己的感受。

- 共同探索:咨询师应该与当事人一起探索他们的感受和想法,而不是单方面地提供解决方案。

-

进一步阐述:

-

咨询关系的价值:咨询关系在面对自杀念头时可以是一个宝贵的资源,帮助咨询师更好地理解和支持对方。

-

进一步阐述:

- 支持系统:良好的咨询关系可以成为当事人的支持系统,帮助他们应对内心的痛苦和困惑。

- 增强韧性:通过建立信任和支持的关系,咨询师可以帮助当事人增强心理韧性和应对能力。

-

进一步阐述:

总结 将自杀念头公开化是咨询过程中非常重要的一环,它有助于及时发现和处理潜在的自杀风险。咨询师在处理自己的感受时,需要认识到自己的情绪反应,并通过挑战自我破坏性想法来保持冷静和专业。建立良好的咨询关系是帮助考虑自杀的人的关键,通过建立信任和开放的沟通,咨询师可以更有效地支持和干预。在实际工作中,咨询师需要不断学习和提升自己的专业素养,以应对各种复杂的自杀危机情况。同时,与主管的咨询和支持也是非常重要的,可以帮助咨询师更好地应对挑战。]

[进一步阐述知识点

1. 关注个体的矛盾心理

-

个体差异:每个咨询师都需要根据自己的情况决定如何咨询有自杀倾向的人。不同的咨询师可能有不同的方法和风格。

-

进一步阐述:

- 个性化方法:每个咨询师都有自己独特的风格和方法,因此在处理有自杀倾向的人时,需要根据自己的经验和专长来选择最合适的方法。

- 灵活性:咨询师需要具备灵活性,能够根据当事人的具体情况调整自己的方法和策略。

-

进一步阐述:

-

直接方法:有些咨询师更喜欢直接的方法,试图说服对方不要自杀,对某些人来说,这可能是最好的方法。然而,这种方法可能使咨询师与当事人对立,不利于建立信任关系。

-

进一步阐述:

- 潜在风险:直接方法可能使当事人感到被指责或不被理解,从而产生抵触心理,不利于建立信任关系。

- 适用性:在某些情况下,直接方法可能有效,特别是当当事人处于极度危机状态时,但需要谨慎使用。

-

进一步阐述:

-

矛盾心理:大多数有自杀念头的人对死亡都有某种程度的矛盾心理。这种矛盾心理表现为他们既想结束生命,又害怕死亡,或者不确定自杀是否是最好的解决办法。

-

进一步阐述:

- 复杂性:自杀念头通常是复杂和矛盾的,当事人可能同时存在多种情感和想法,如恐惧、绝望、希望和矛盾。

- 探索矛盾:通过探讨当事人的矛盾心理,咨询师可以帮助他们更全面地看待问题,找到其他解决办法。

-

进一步阐述:

-

建立关系:专注于建立与当事人的关系,通过探讨他们的矛盾心理,帮助他们更全面地看待问题。这种方法可以减少对立,增强信任,使当事人更愿意打开心扉,讨论自己的感受和想法。

-

进一步阐述:

- 信任基础:建立信任关系是咨询过程的基础,有助于当事人更愿意分享自己的内心世界。

- 积极倾听:通过积极倾听和共情,咨询师可以更好地理解当事人的感受和需求,提供更有效的支持。

-

进一步阐述:

-

成功咨询的钥匙:专注于个体间的咨询关系,同时探讨当事人的矛盾心理,往往是成功咨询有自杀倾向者的钥匙。通过这种方式,咨询师可以更好地理解当事人的内心世界,提供更有效的支持和干预。

-

进一步阐述:

- 综合方法:结合建立信任关系和探讨矛盾心理,可以更全面地帮助当事人处理自杀念头。

- 个性化支持:通过理解当事人的内心世界,咨询师可以提供个性化的支持和干预,帮助他们找到新的希望和意义。

-

进一步阐述:

表34.1 自我破坏性陈述与有益自我陈述的对比

| 自我破坏性陈述 | 有益自我陈述 |

|---|---|

| 如果这个人自杀,我是个人负责。 | 令人遗憾的是,从长远来看,如果一个人坚定地决定自杀,没有人能阻止他们。最终这是他们的选择。 |

| 我应该一直陪着这个人,直到他们不再有自杀念头。 | 我不可能24小时全天候看护这个人。从长远来看,他们必须对自己负责。然而,如果我愿意并且有能力,我可以安排适当的 psychiatry 监督。 |

| 如果我足够有技巧,我有能力改变这个人的想法。 | 或者:我必须说服这个人不要自杀。 |

| 我不如其他咨询师合格。 | 我就是我,有我的技能和局限。如果我能将这个人转介给更有资格的人,我会这么做。在此期间,我会尽我最大的努力。 |

| 如果我无能,我会对这个人的死亡负责。 | 在如此紧张的情况下,期望自己成为完美的咨询师是不现实的。我不能为他们的决定负责,我只能做我力所能及的事。 |

| 我必须满足这个人的期望。 | 我不需要满足这个人的期望。 |

| 我应付不来。 | 只要我设定现实的期望,我就能应付。 |

总结

关注个体的矛盾心理是咨询有自杀倾向者的重要方法。咨询师需要根据自己的情况选择合适的方法,建立与当事人的信任关系,探讨他们的矛盾心理。通过这种方式,咨询师可以更好地理解当事人的内心世界,提供更有效的支持和干预。同时,咨询师也需要处理自己的感受,避免自我破坏性思维,保持专业和冷静。在实际工作中,与主管的咨询和支持也是非常重要的,可以帮助咨询师更好地应对挑战。 ]

进一步阐述知识点

1. 关注个体的矛盾心理

- 个体差异:每个咨询师都需要根据自己的情况决定如何咨询有自杀倾向的人。不同的咨询师可能有不同的方法和风格。

- 直接方法:有些咨询师更喜欢直接的方法,试图说服对方不要自杀,对某些人来说,这可能是最好的方法。然而,这种方法可能使咨询师与当事人对立,不利于建立信任关系。

- 矛盾心理:大多数有自杀念头的人对死亡都有某种程度的矛盾心理。这种矛盾心理表现为他们既想结束生命,又害怕死亡,或者不确定自杀是否是最好的解决办法。

- 建立关系:专注于建立与当事人的关系,通过探讨他们的矛盾心理,帮助他们更全面地看待问题。这种方法可以减少对立,增强信任,使当事人更愿意打开心扉,讨论自己的感受和想法。

- 成功咨询的钥匙:专注于个体间的咨询关系,同时探讨当事人的矛盾心理,往往是成功咨询有自杀倾向者的钥匙。通过这种方式,咨询师可以更好地理解当事人的内心世界,提供更有效的支持和干预。

表34.1 自我破坏性陈述与有益自我陈述的对比

总结

关注个体的矛盾心理是咨询有自杀倾向者的重要方法。咨询师需要根据自己的情况选择合适的方法,建立与当事人的信任关系,探讨他们的矛盾心理。通过这种方式,咨询师可以更好地理解当事人的内心世界,提供更有效的支持和干预。同时,咨询师也需要处理自己的感受,避免自我破坏性思维,保持专业和冷静。在实际工作中,与主管的咨询和支持也是非常重要的,可以帮助咨询师更好地应对

进一步阐述知识点

探讨个体的选择

选择的代价

- 失去选项:当一个人在两个选项之间做出选择时,他们将失去其中一个选项。选择自杀意味着失去生命、与他人的联系以及与他人交流痛苦的机会。

- 未来希望:如果他们对未来抱有任何希望,这些希望也会消失。

- 死亡的成本:死亡的成本可能包括对未知的恐惧,对于一些宗教人士来说,还包括因自杀而受到惩罚的恐惧。

矛盾心理的重要性

- 意识到矛盾心理:让考虑自杀的人意识到他们的矛盾心理,并帮助他们审视死亡和生活的后果、成本和收益是非常重要的。

- 避免对立:直接施压让当事人活下去可能会导致咨询师与当事人之间的对立,因此我们尽量避免这种情况。

- 建立关系:通过与当事人一起探索他们的选择,他们可能会感到被理解,有机会处理他们的痛苦,并可能感到足够被重视,从而重新考虑他们的决定。

咨询师的角色

- 陪伴和探索:咨询师需要陪伴当事人,让他们自由地探索“我想死”这一部分自我及其对立面。

- 充分探索:一个人需要充分探索他们的自毁性想法,才能改变这些想法。

直接方法

方法概述

- 说服活着:直接方法是试图说服考虑自杀的人,活着是最好的选择。

- 潜在问题:这种方法可能在说“我想死”的人和说“我希望你活”的咨询师之间引发争斗,需要施加巨大压力来说服当事人生活的正确性,而这可能很困难。

选择合适的方法

- 个体差异:没有普遍的“正确方法”,每个人都是独特的,每个咨询师也是如此。

- 建立关系:如果咨询师专注于建立和维护稳固的个人与个人之间的咨询关系,那么他们就优化了成功的可能性。

- 职责要求:当这种方法不成功时,职责要求咨询师采取行动,在与主管协商后确保当事人的安全和福祉。

应对抑郁和愤怒

抑郁的根源

- 被压抑的愤怒:考虑自杀的人通常处于深深的抑郁中,抑郁通常是由于被压抑的愤怒引起的。

- 内化愤怒:有时,考虑自杀的人可能将本应适当地指向他人的愤怒转向自己。

重新框架

- 问“你对谁生气?”:问“你对谁生气?”这个问题可能有用。如果当事人回答“我自己”,你可以同意这一点,并指出这与想要自杀是一致的。

- 重新框架自杀:将自杀视为自我惩罚而非逃避的重新框架在某些情况下可能有助于产生变化。

- 转移愤怒:然后你可以问,“除了你自己,你还对谁最生气?”如果通过这种方式你能帮助当事人表达他们的愤怒,并将其从自己身上转移到其他人身上,他们的抑郁和自杀念头可能会减轻。

咨询师的责任

- 确保安全:作为咨询师,你必须尽最大努力确保寻求你帮助的当事人不会对他人构成威胁。

通过上述内容,作者希望帮助读者更好地理解在咨询过程中探讨个体选择、处理矛盾心理、选择合适的方法以及应对抑郁和愤怒的重要性。这些知识点不仅有助于咨询师更好地支持当事人,还能提高咨询的效果,确保当事人的安全和福祉。

进一步阐述知识点

学习总结

重复自杀企图的风险

-

高风险群体:经常重复自杀企图的人最终往往能够成功自杀。这类人群包括:

- 陷入悲惨生活的人:长期生活在不幸和痛苦中的人。

- 最近经历过创伤的人:近期遭受重大打击或创伤的人。

- 试图操纵他人的人:通过自杀威胁来达到某种目的的人。

咨询师的自我处理

- 处理个人感受:在咨询自杀者时,咨询师需要处理自己的感受,如恐惧、无助和焦虑。

- 挑战非理性信念:咨询师需要识别并挑战自己可能存在的非理性信念,如“我必须拯救每个人”或“如果我失败了,就是我的错”。

咨询技巧的应用

- 了解触发因素:了解是什么触发了当事人的自杀念头,这有助于找到问题的根源。

- 关注愤怒:将当事人的愤怒带入焦点,帮助他们表达和处理愤怒情绪。

- 抓住矛盾心理:如果有用,抓住当事人的矛盾心理,帮助他们看到生活的另一面。

- 探讨选择和成本:探讨当事人的选择,特别是死亡的成本,包括对家人、朋友和社会的影响。

- 直接对抗的方法:如果认为直接对抗的方法更有可能有效,可以使用,但需谨慎。

- 采取直接行动:决定采取哪些直接行动以防止自杀,如联系紧急服务或安排住院。

- 转介专业人士:尽可能将当事人转介给合适的专业人士,如精神科医生或心理治疗师。

进一步阅读

-

Duffy, D. & Ryan, T. (编) 2004, 预防自杀的新方法:从业者手册, Jessica Kingsley, 伦敦.

- 本书提供了多种预防自杀的新方法和实用技巧,适合专业人士参考。

-

Henden, J. 2008, 预防自杀:解决方案聚焦方法, Wiley, 奇切斯特.

- 本书介绍了解决方案聚焦的方法,帮助咨询师在预防自杀的过程中更有效地支持当事人。

-

Reeves, A. 2010, 咨询自杀客户, SAGE, 伦敦.

- 本书详细介绍了如何在咨询中处理自杀客户,提供了丰富的案例和实际操作建议。

通过上述内容,作者希望帮助读者更好地理解在咨询过程中处理自杀者的关键点,包括识别高风险群体、处理咨询师的个人感受、应用有效的咨询技巧以及采取必要的行动。这些知识点不仅有助于咨询师更好地支持当事人,还能提高咨询的效果,确保当事人的安全和福祉。

进一步阐述知识点

学习总结

重复自杀企图的风险

-

高风险群体:经常重复自杀企图的人最终往往能够成功自杀。这类人群包括:

- 陷入悲惨生活的人:长期生活在不幸和痛苦中的人。

- 最近经历过创伤的人:近期遭受重大打击或创伤的人。

- 试图操纵他人的人:通过自杀威胁来达到某种目的的人。

咨询师的自我处理

- 处理个人感受:在咨询自杀者时,咨询师需要处理自己的感受,如恐惧、无助和焦虑。

- 挑战非理性信念:咨询师需要识别并挑战自己可能存在的非理性信念,如“我必须拯救每个人”或“如果我失败了,就是我的错”。

咨询技巧的应用

- 了解触发因素:了解是什么触发了当事人的自杀念头,这有助于找到问题的根源。

- 关注愤怒:将当事人的愤怒带入焦点,帮助他们表达和处理愤怒情绪。

- 抓住矛盾心理:如果有用,抓住当事人的矛盾心理,帮助他们看到生活的另一面。

- 探讨选择和成本:探讨当事人的选择,特别是死亡的成本,包括对家人、朋友和社会的影响。

- 直接对抗的方法:如果认为直接对抗的方法更有可能有效,可以使用,但需谨慎。

- 采取直接行动:决定采取哪些直接行动以防止自杀,如联系紧急服务或安排住院。

- 转介专业人士:尽可能将当事人转介给合适的专业人士,如精神科医生或心理治疗师。

进一步阅读

-

Duffy, D. & Ryan, T. (编) 2004, 预防自杀的新方法:从业者手册, Jessica Kingsley, 伦敦.

- 本书提供了多种预防自杀的新方法和实用技巧,适合专业人士参考。

-

Henden, J. 2008, 预防自杀:解决方案聚焦方法, Wiley, 奇切斯特.

- 本书介绍了解决方案聚焦的方法,帮助咨询师在预防自杀的过程中更有效地支持当事人。

-

Reeves, A. 2010, 咨询自杀客户, SAGE, 伦敦.

- 本书详细介绍了如何在咨询中处理自杀客户,提供了丰富的案例和实际操作建议。

通过上述内容,作者希望帮助读者更好地理解在咨询过程中处理自杀者的关键点,包括识别高风险群体、处理咨询师的个人感受、应用有效的咨询技巧以及采取必要的行动。这些知识点不仅有助于咨询师更好地支持当事人,还能提高咨询的效果,确保当事人的安全和福祉。

危机电话咨询和面对面咨询的区别是什么? 咨询师在与有自杀想法或倾向的人进行咨询时需要具备哪些技能? 咨询师需要了解哪些法律法规? 如何避免咨询有自杀倾向者的自我破坏性思维? 如何处理咨询有自杀倾向者的不满情绪? 如何评估咨询有自杀倾向者的进展?```

34 Responding to suicidal intentions

Crisis telephone counselling services frequently get calls from people who are contemplating suicide and sometimes callers have already overdosed on prescribed medication before ringing for help. Also face-to-face counsellors will inevitably be confronted at times by people who have suicidal thoughts or tendencies. Most, it not all, counsellors are anxious when counselling such people, and working with them is inevitably stressful.

ETHICAL ISSUES 1 here are ethical issues involved when dealing with a pei’son who is contemplating suicide, and before choosing strategies that are acceptable to you, as a counsellor, you may need to clarify your own values with regard to suicide. As counsellors, it is desirable that, if possible, we do not impose our own values on the people who seek help. However, we do need to be congruent and genuine, so each of us needs to do whatever is necessary’ to satisfy7 our own conscience. In addition, we need to be aware of any legal obligations and the legal implications of our actions. We must remember that we owe a duty of care to every7 person who seeks our help and that we need to respect the policies of the agency for which we work. If there are internal conflicts for us when dealing with a pei’son who is contemplating suicide, then we need to resolve these for both our own wellbeing and theirs.

Counsellors have a duty of care to those who seek their help

Does a person have the right to take their own life if they choose to do so? Your answer to this question may differ from Olli’s, and our answers may differ from those of a pei’son who seeks our help. We suggest that you discuss this question in depth with your training group if you are in one, or with your supervisor, so that you have a clear idea of your own attitudes and beliefs regarding suicide and of your supervisor’s expectations. You will then be better equipped to help a person who has suicidal thoughts. We recognise that some counsellors believe that a person has the right to kill themselves if, after careful consideration, they choose to do so. However, most counsellors strongly oppose this view and believe that firm intervention is justifiable and necessary7 to prevent suicide from occurring. Many counsellors believe that a person who is contemplating suicide may be temporarily emotionally disturbed and not capable of making a rational decision at that time. This belief is reinforced by experiences with people who were suicidal and then later have thanked the counsellor, because they have found new meaning and satisfaction in their lives. Consequently, most counsellors believe that a counsellor s duty of care justifies the need for firm intervention, involuntary hospitalisation and subsequent psychiatric treatment where other options fail. Clearly, there are duty of care issues involved because suicide involves a one-way journey, and people who have suicidal thoughts need to be taken seriously. Remember that people who repeatedly make suicide attempts often succeed in killing themselves eventually. Their cry for help needs to be heard before it is too late.

REASONS FOR CONTEMPLATING SUICIDE People who are considering suicide broadly fall into four categories, although three of these overlap to some extent. The first category comprises people whose quality of life is terrible, and who see little or no possibility7 for improvement. Included in this category are people who are chronically ill, in chronic pain, seriously disabled and/or in extreme poverty’ with little possibility7 of changing their situations. Such people are often severely depressed and are seriously at risk of ending their lives because they can see little reason for living. This is particularly so if they are alone and do not have adequate social support. The second category7 includes people who have experienced a recent trauma. These people are very much at risk around their time of crisis. Included in this category are people who have suffered losses such as those described in Chapter 32. fhe third category comprises people who use suicidal talk or suicidal behaviour as a last resort in an attempt to get others to hear or respond to their pain. Sometimes their goal is to manipulate the behaviour of others. They are still genuinely at risk, but their motivation is different. They often have considerable ambivalence towards dying and may not really want to die. Some people in this categoiy are openly manipulative and, for example, might say to a spouse who has left them, ‘Come back to me or 1 will kill myself. I he fourth categoiy includes people who are having a psychotic episode and may be hearing voices that tell them to kill themselves. Clearly, these people need urgent psychiatric help.

The first step in helping is to try to understand the person s current thinking

We have drawn up a list of possible reasons why a person might contemplate or talk about the possibility of suicide. As you read the list you may wish to think about whether there might be other reasons which have not been included. Possible reasons include: • because they despair of their situation and are unable to see an alternative solution to their problems, which seem to them to be unsolvable, intolerable and inescapable • because they are emotionally disturbed, are afraid that they may commit suicide and want to be stopped • to make a statement • as a way of hurting others; an ultimate expression of anger • to make a last-ditch effort to draw attention to a seemingly impossible situation, when other methods have failed to manipulate someone else because they have positively decided to commit suicide, want to do it and want other people to understand the reasons for the proposed action to be in contact with another human being prior to, or while, dying to say 'Goodbye’, as preparation for death because they are having a psychotic episode and are hearing voices telling them to kill themselves.

ASSESSMENT OF RISK OF SUICIDE Anyone who says that life is not worth living may be at some level of risk. However, many people who have no intention of killing themselves experience times when they despair and start to question die value of their lives. A difficulty for counsellors is to determine the level of risk for a particular person. It is here that experience can be helpful in estimating level of risk, in deciding whether action needs to be taken or not, and in choosing the action to take, if action is needed. Consequently, new counsellors need to consult with their supervisors.

When assessing the level of risk it can be helpful to consult with your supervisor

There are some factors that are commonly considered in the relevant literature to be useful in determining level of risk (see the further reading suggested at the end of this chapter). A number of risk factors will now be discussed. GENDER AND ETHNICITY Although women attempt suicide more often than men, males are associated with higher risk. This is because males are more often successful in completing suicide than females. In particular, in Australia, Aboriginal males are associated with high risk. AGE Suicide is more likely to occur in the young and the old, with the risk being higher in people up to the age of 18 years and above 45. INTENSE OR FREQUENT THOUGHTS OF SUICIDE Whenever a person thinks of suicide it is wise to assume that there is some level of risk. However, if the thoughts are persistent or strong with little ambivalence, risk is increased.

WARNING SIGNALS People who commit suicide have often given out warning signals over a period of time. Unfortunately, sometimes these are disregarded because they may have been given many times and been seen incorrectly as threats that will not be carried out.

HAVING A SUICIDE PLAN If a realistic plan for committing suicide has been developed, then clearly the person has moved beyond vague thoughts that life is not worth living and there is a real risk that the plan may be carried out.

CHOICE OF A LETHAL METHOD Some methods of committing suicide are more likely to reach completion than Others because they are quick or provide little opportunity for withdrawal if the person concerned has a change of mind as death approaches. Examples are when a person uses a gun or jumps off a high building.

AVAILABILITY OF METHOD Risk is higher if the person already has the means to carry out the plan. For example, if a person has a loaded gun, or enough pills to cause death, then the plan may be carried out.

DIFFICULTY OF RESCUE Risk is increased in cases where it would be difficult for others to intervene and prevent the suicide attempt. Examples are where a person is in an isolated place, when the location is unknown or when someone has climbed a structure, making it difficult for others to follow.

BEING ALONE AND HAVING LACK OF SUPPORT People who are alone, single or separated, and believe that no one cares for them, are vulnerable to depression and suicidal thoughts and action. It may also be easier for them to cany out a suicidal plan without interference.

PREVIOUS ATTEMPTS Previous attempts are an indication of increased risk. This is particularly so if the attempts have been frequent, are recent and have been serious.

A FRIEND OR FAMILY MEMBER HAS DIED OR COMPLETED SUICIDE Risk of suicide is increased where a family member, close friend, colleague or peer has completed suicide. Additionally there may be risk where a loved one or pet has died.

LISTENING TO SONGS ABOUT DEATH Some people, particularly the younger members of society, tend to listen obsessively to songs about death, dying and suicide. This increases risk.

DEPRESSION People who are depressed, feel hopeless, helpless or in despair are at risk. Phis is particularly so with severe depression where there may be symptoms such as loss of sleep or an eating disturbance.

PSYCHIATRIC HISTORY Psychiatric illness or history is another indication of increased risk.

LOSS OF RATIONAL THINKING Loss of rational thinking can occur for a variety of reasons. People who have been traumatised, are under the influence of alcohol or drugs, are suffering from dementia or have a psychiatric disorder may not be capable of thinking rationally. They therefore present increased risk and there are clear duties of care for the counsellor.

UNEXPLAINED IMPROVEMENT Someone who has been exhibiting severely depressed feelings with suicidal thoughts and then suddenly changes to display a calmness and sense of satisfaction for no recognisable reason may be at Very high risk. The person may have completed preparations for suicide and have a sense of relief at the thought of their planned escape from acute emotional pain. By convincing the counsellor that everything is now OK, they may effectively mislead the counsellor so that preventative action is not taken.

GIVING AWAY POSSESSIONS AND FINALISING AFFAIRS Behaviours such as giving away personal possessions, making a new will or terminating a lease may be an indication that the person is preparing for suicide and at high risk.

MEDICAL PROBLEMS Medical problems that severely interfere with quality of life, are painful or are life threatening increase the risk of suicide. Chronic illness with little perceived hope of a cure or respite may increase a person s desire to terminate life. Here, there are both values and duty of care issues, as some people firmly believe that voluntary7 euthanasia is morally justifiable while others strongly disagree.

SUBSTANCE ABUSE Excessive use of alcohol or drugs, both illegal and legally prescribed, raises the suicide risk. Certainly, alcohol or other substance abuse is associated with completed suicides.

RELATIONSHIP PROBLEMS People who believe that they are locked in to highly dysfunctional relationships and cannot leave are at increased risk. Similarly, there may be risks for people whose relationships are breaking up, who are separating or separated, and for those who are going through the process of divorce. When relationships change through, for example, remarriage, moving into a new stepfamily, having a new child in the family or children leaving the family, there may be an increased risk.

CHANGES IN LIFESTYLE OR ROUTINE Many people find it difficult to adjust to changes in their lifestyle or routine, so times of change can precipitate suicidal thoughts and increased risk. Examples are when a person changes job, school or their place of residence. This may be particularly relevant when a person moves to a new locality and may lose access to long-term friends.

FINANCIAL PROBLEMS Issues involving poverty, unemployment and financial difficulties, where the person concerned is depressed and feeling helpless to change the situation, lead to an increased risk. Important examples are bankruptcy and cases where a person loses a business or home.

TRAUMA AND ABUSE Traumatic events and the experience of abuse or perceived abuse, in both the past and the present, may contribute to suicide risk. I his includes emotional, physical, sexual and social abuse.

LOSS All losses of importance contribute to suicide risk. Examples include loss of a significant relationship, job, employment opportunities, business, home, possessions, self-esteem and loss of role. People who experience failure either at work or academically, or believe that they have failed others, are likely to suffer loss of self-esteem. The risk factors that have been discussed are included in Figure 34.1. 1 his may be photocopied for personal use and used as an aid in identifying risk factors when counselling people with suicidal thoughts or tendencies. However, it must be remembered that there is no precise formula for assessing risk, because we human beings are each unique, possessing our own individual qualities. All talk of suicide needs to be taken seriously and appropriate help sought where necessary.

COUNSELLING STRATEGIES Perhaps the biggest problem for a new counsellor when seeking to help a person troubled by suicidal thoughts is the counsellor’s own anxiety. Sometimes new counsellors will tty to deflect a person away from suicidal talk rather than encouraging them to bring their self-destructive thoughts out into the open and deal with them appropriately. Unfortunately, such avoidance of the issue may increase the likelihood of a suicide attempt.

Figure 34.1 Assessment of suicide risk Risk factors - tick boxes where risk is indicated □ Gender □ Age □ Ethnic background□ Medical problems □ intense and/or frequent thoughts of suicide □ Warning signals given out over a period of time □ Has a suicide plan □ Choice of a lethal method □ Availability of method □ Difficulty of rescue □ Is isolated or alone □ Lack of support□ Significant life-changing events □ Change in lifestyle and/or routine □ Change in job, school or house locality □ Previous suicide attempts □ A friend, peer, colleague or family member has completed suicide □ Listening obsessively to songs about death, dying or suicide □ Death of loved one, friend or pet □ Depression □ Psychiatric illness or history □ Loss of rational thinking □ Unexplained improvement □ Giving away possessions □ F inalising affairs □ Relationship highly dysfunctional □ Relationship break up, separation or divorce □ Relationship changes - remarriage, new stepfamily, addition of new child, children leaving family □ Relationship worries -■ fear of losing a family member or partner or that someone is not coping □ Alcohol and/or drug abuse □ Financial problems □ Socioeconomic situation □ Trauma □ Abuse or perceived abuse — emotional, physical, sexual or social abuse in the past or the present □ Loss of employment or employment opportunities □ Loss of business, home or possessions □ Loss of self-esteem — feeling a failure at work or academically — or belief that others have been let down □ Loss of role □ Other factors not listed

BRING SUICIDAL THOUGHTS INTO THE OPEN Whenever counselling a depressed or anxious person, counsellors need to look for the smallest clues that might suggest that the person may be contemplating suicide. People are often reluctant to say "I would like to kill myself. They tend instead to be less specific and to make statements such as ' 1 don’t enjoy life anymore’ or ‘I’m fed up with living.' When a person makes a statement such as this, it is sensible for the counsellor to be direct, and ask them, ‘Are you thinking of killing yourself?' In this way, suicidal thoughts are brought out into the open and can be dealt with appropriately. We need to remember that a significant proportion of people are at some times in their lives ambivalent about wanting to live and that many consider the possibility of committing suicide before rejecting it.

It can be advantageous to be direct when exploring suicidal thoughts

DEAL WITH YOUR OWN FEELINGS You will be a very’ unusual person indeed if you don't become emotionally tense when a person tells you that they are thinking of killing themselves. As a counsellor, allow yourself to experience your feelings and then you will be able to decide what to do about them. It is likely that these feelings may result from you giving yourself unhelpful messages such as those listed in Table 34.1. If so, you can give yourself new messages, after discarding the self-destructive messages that may be contributing to your tension. Table 34.1 presents some typical self-destructive and alternative helpful self statements for the situation. Challenge your self-destructive thoughts, and if your feelings of tension don’t subside, consult your supervisor.

COUNSELLING SKILLS I he micro-skills that have been learnt previously, together with an appropriate counselling relationship, are the basic tools for helping a person who is contemplating suicide. We suggest that initially it is important to concentrate on building a relationship with the person, so that when trust has been established they can talk openly about their feelings and intentions. The counsellor might invite them to do this by saying, ‘I am concerned for your safety and wellbeing, and it is important for me to understand fully how and why you feel the way you do.' By taking this approach the person is likely to recognise that the counsellor is joining with them in the exploration of their feelings, thoughts and options, rather than working in opposition to them.

The counselling relationship can be a valuable resource when confronting suicidal thoughts

FOCUS ON THE PERSON'S AMBIVALENCE We recognise that each individual counsellor needs to make a decision for themselves about how to counsel a suicidal person. Some counsellors prefer a direct

Table 34.1 Comparison between self-destructive and helpful self-statements for counsellors seeking to help people with suicidal thoughts SELF-DESTRUCTIVE STATEMENTHELPFUL SELF-STATEMENT 1 am personally responsible if this person completed suicide.Sadly in the long term, no one can stop this person from killing themselves if they firmly decide to do that. Ultimately it will be their choice. 1 should stay with the person until they no longer have suicidal thoughts.It's impossible for me to watch over the person 2.4 hours a day. In the long term they have to be responsible for themselves. However, if 1 wish, and am able, 1 can take steps to arrange appropriate psychiatric supervision. 1 have the power to change this persons mind if 1 am skilful enough. OR 1 must persuade this person not to suicide.1 don't have the power to change someone else's mind, ThW most 1 can do is to help them explore the issues involved, and then take any other action available to me. I'm not as well qualified as other counsellors.1 am me, with my skills and limitations. If 1 am able to refer this person on to someone more qualified 1 will, and in the meantime I II do my best. If 1 am incompetent 1 will be to blame for this person's death.It's unrealistic for me to expect to be a perfect counsellor in such a stressful situation. 1 cannot take responsibility for their decision. 1 can only do what 1 am capable of doing. 1 must Live up to the person's expectations.1 do not need to live up to the person's expectations. 1 can't cope.1 can cope provided that i set realistic expectations for myself. approach where they will try to convince the person that they should not kill themselves, and for some people this may be the best approach. However, in our view this is not always the best approach because it puts the counsellor in opposition to the person. We think that usually it is more useful to focus on building a relationship with the person and then exploring their ambivalence — 'Should I kill myself or not?1 Most, if not all, people with suicidal thoughts have some degree of ambivalence towards dying. If a person was 100 per cent convinced that they wanted to kill themselves, they probably wouldn't be talking to a counsellor; they would just go ahead with their suicide plan. We have found that focusing on the person-to- person counselling relationship while exploring the person's ambivalence is often the key to the successful counselling of those who are contemplating suicide. EXPLORING THE PERSON'S OPTIONS As explained in Chapter 25, when a person chooses between two alternatives they lose one of the options and may also have to pay a price for the chosen option. By choosing suicide, a person loses life, contact with others and the opportunity to communicate with others about their pain. In addition they lose hope, if they had any, for a better future. The cost of dying is likely to include fear of the unknown and for some religious people fear of being punished for killing themselves. We think that in many situations it can be advantageous to make a person who is contemplating suicide aware of their ambivalence, and to help them to look at the consequences, costs and pay-offs of dying and of living. Although at some stage we may decide that duty of care requires the use of firm intervention, in the first instance we try to avoid directly pressuring the person to stay alive and instead help in the exploration of their options. In this way the person is likely to feel understood, has the opportunity'’ to work through their pain and may feel sufficiently valued to enable them to reconsider their decision.

By joining with the person, they are free to explore both the 41 want to die1 part of self and the opposite polarity, with the counsellor walking alongside during the exploration.

A person needs to fully explore their self-destructive thoughts in order to be able to change them

THE DIRECT APPROACH The direct approach is to try to persuade the person who is contemplating suicide that living is the best option. This approach is not usually our first preference because it sets up a struggle between the person who is saying ‘I want to die’ and the counsellor who is saying ‘I want you to live’. There is then heavy pressure on the counsellor to convince the person of the rightness of living, and this may be difficult as the counsellor and the person are in opposition rather than joining together. Even so, this approach can be successful with some people. There is no universal 'right way’ to go. Every’ person is unique and so is every’ counsellor. Each counsellor needs to choose an approach that seems right for them and for the person who is seeking their help. If a counsellor concentrates on establishing and maintaining a sound person-to-person counselling relationship, then they optimise the chances of success. Where this approach is not successful, duty of care requires the counsellor to take action, in consultation with their supervisor, to ensure the person’s safety and wellbeing.

DEALING WITH DEPRESSION AND ANGER People who are contemplating suicide are usually in deep depression, and depression, as explained in Chapter 31, is often due to repressed anger. Sometimes a person who is contemplating suicide may be turning anger, which could be appropriately directed at others, inward and towards themselves. It may be useful to ask the question 'Who are you angry with?’ If the person replies by saying 'Myself, you can agree that that is obvious and consistent with wanting to suicide. You might say, ‘You are so angry with yourself that you want to punish yourself by killing yourself.’ 1 his reframe of suicide as self-punishment rather than escape may be useful in some cases in helping to produce change. You could then ask, ‘After yourself, who are you most angry with?’ If by doing this you can help the person to verbalise their anger and direct it away from themselves and onto some other person or persons, their depression and suicidal thoughts may moderate. However, it is important to remember that as a counsellor it is important to do your best to ensure that the person who seeks your help is not a danger to others.

LOOKING FOR THE TRIGGER Another way of entering a person’s world is to find out what triggered off the suicidal thoughts today. Very often a single event is the trigger and this trigger can sometimes give important clues about the person’s intentions. For example, is the person’s intention pa illy to punish someone who has angered or hurt them? If so, it might be useful to explore the issues involved.

CONTRACTING After working through the relevant issues with a person who has been troubled by suicidal thoughts, many counsellors encourage the person to sign a contract to agree that if strong suicidal thoughts return they will not kill themselves before coming back for counselling. Although we ourselves do not use written contracts, we do negotiate with such people to obtain a verbal agreement about what action they will take if strong suicidal thoughts recur. We explore alternatives with them regarding the help they might seek if they start to feel tempted again to commit suicide. We ask them who is the first person they would try to contact, and if that person wasn’t available who else could they contact, or where would they go for help, in seeking a verbal agreement we rely on the strength of the counselling relationship, making it clear that the person is important to us and that we believe that we can trust them to honour the agreement.

RECOGNISE YOUR LIMITATIONS Don’t forget that it is unrealistic, unfortunately, to expect that a person will necessarily decide to stay alive. Although you may be able, if you choose, to take measures to ensure that the person stays alive in the short term, in the long term, if they are determined to kill themselves, they are likely to succeed. However, as counselling progresses you will need to decide, in consultation with your supervisor, whether direct action to prevent suicide is warranted and necessary. This decision is a heavy one and is certain to be influenced by your own values and those of the agency that employs you. There are some cases where the decision to intervene is clear. It would, for example, be unethical and irresponsible to allow someone who was psychologically disturbed due to a temporary psychiatric condition or a sudden trauma to kill themselves without determined and positive action being taken to stop them. A person who is seriously contemplating suicide is likely to need ongoing psychotherapy from a skilled professional, so be prepared to refer appropriately. 1 he eventual wellbeing of such a person depends on them being able to make significant changes to their thinking and way of living, and this is unlikely to be achieved in one counselling session.

In some cases our duty of care demands firm direct action

Learning summary People who make repeated suicide attempts often succeed m killing themselves. Suicidal people include those who are locked into miserable lives, those who have recently experienced trauma, and those who want to manipulate others. When counselling a suicidal person, it is important to deal with your own feelings as a counsellor and to challenge any irrational beliefs you may have. When counselling a person who is contemplating suicide, focus on the counselling relationship using the normal counselling micro-skills: » find out what triggered the suicidal thoughts » bring the persons anger into focus » hook into the person's ambivalence if that can be useful » explore the person's options and particularly the costs of dying » use a more direct confrontational approach if you think that it is more likely to be effective » decide what direct action is warranted and necessary to prevent suicide » whenever possible, refer to suitably qualified professionals.

Further reading Duffy, D. & Ryan, T. (eds) 2004, Xew Approaches to Preventing Suicide: A Manual for Practitioners, Jessica Kingsley, London. Henden, J. 2008, Preventing Suicide: The Solution Focused Approach, Wiley, Chichester. Reeves, A. 2010, Counselling Suicidal Clients, SAGE. London.